WHERE WAS THE KITCHEN?

Written by Gwen Sinclair

We’re certain that there would have been something cooking in the kitchens here at Royal Dundonald Castle at the time of Robert II (1371-1390)- indeed the Castle is thought to have not only been the favourite place of Robert II, but also served as his hunting lodge. Let’s imagine the great feasts which would’ve taken place within its walls, and its castle kitchens would’ve been accustomed to creating fine dining from the choice of locally caught game or fish – which Robert himself may have provided after a day’s hunting in what would have been an vast extension of the ancient forests which survive here today. He may well have hunted with a falcon, which we know was a popular method of catching smaller game in medieval times. Once the hunters returned the castle, cooks would have then been expected to prepare feasts for the king and his household.

This would have been an herculean task since King Robert II would’ve had a large contingency of guards for the exceptionally high level of security required for both for himself, and his family of 21 children, as well as his wife, Queen Euphemia and her ladies. Let’s also add the King’s Steward, Councillors, clergymen, knights, scribes and any number of other members required for his royal household, including servants, craftsmen, blacksmiths, apothecaries and stable hands, to name just a few – in our estimate there could have easily been well over 50 people requiring to be fed each day! From this, we might imagine that Royal Dundonald Castle kitchens would have had to be fairly extensive in order to prepare the exemplary feasts required for the King, his entourage and any visiting high-ranking nobles!

However, it has never been absolutely certain exactly where the kitchens at Royal Dundonald Castle were located, and in this, our latest in the Mysteries of Dundonald Castle Series, we thought we would take a look at trying to find some answers to this age old question!

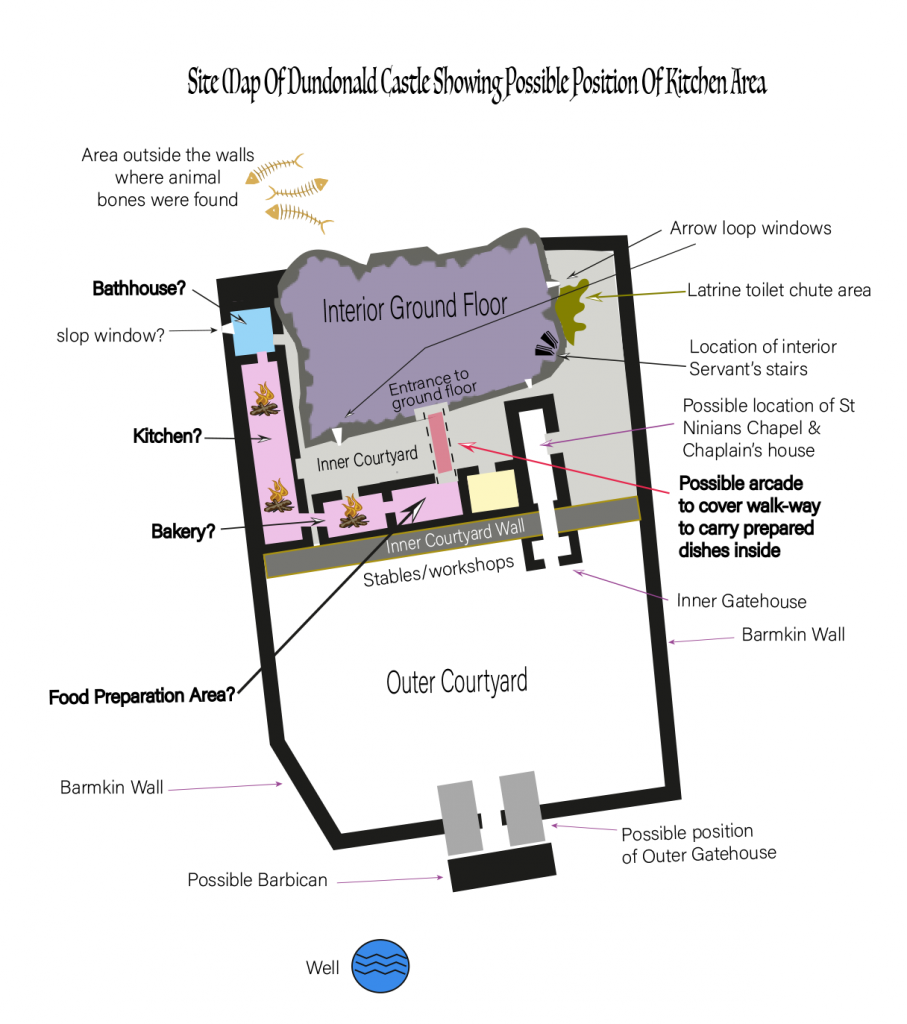

Lets begin by looking at the layout of the building itself to see if we can find any clues there:

It seems that in the building of any castle, there were no blue print plans rolled out across the land, and so each castle was tailor-made to suit the needs of its occupants. We can see that high priority for Dundonald Castle was security against attack, which we find from the remains of the Barmkin wall, which would have stood at an impressive several metres high, and surrounding both courtyards. We also find there is an inner court yard wall which would have provided an additional inner-defence, and that would have contained another access gate to get into the inner court yard and castle entrance.

We also know that the food storage, and kitchens were placed within this extra-defended inner court yard in castles of this time – in case of siege – which meant that even if the occupants were unable to leave for quite some time, there would still have had access to food! ( Indeed this point leads us to another Mystery of Dundonald Castle which is that -as you can see from the bottom left hand corner of the diagram above- the water supply, which would have come from the well, is placed outside the Barmkin Wall! This will be the subject of another in our mystery series coming soon!)

So from this we might deduce that the castle kitchens were located inside the parameters of the inner courtyard – either inside the lower level of the castle – since the upper two levels were great halls – the first being used for dining and the second as the king’s private apartments – or that they were located outside somewhere beyond the castle entrance…

So before we go any further with our investigation, it will be useful to watch this short film where Tour Guide Dave Taylor shows us the ground floor area in question and shares some of his thoughts on the mystery of the kitchens:

So now let’s look at the possibility of them being on the ground floor level:

This is accessed where the entrance to the tower house is now. If we can imagine it with a stone or wooden ceiling suspended above, as remaining joist pockets in the North wall imply, and yet with only 2 narrow arrow loop windows allowing for very little levels of light into the whole lower level, then even with candle light, it would’ve been very dark indeed! Since medieval cooking took place over an open flame, using a large cooking pot or cauldron, or a spit – so it would’ve been an unimaginably smelly, smoky place! Bearing in mind that this was the home of the King, these smells would not have been at all welcome if they wafted up the servants stairs- located at the far corner of the lower level – reaching the Laigh Hall above where the King and his company would’ve dined.

Furthermore, few medieval castle kitchens have survived over time, which might be because cooking done over an open fire always ran the risk of a fire escaping the confines of the hearth, and setting the whole kitchen alight! It really wouldn’t do for a fire in the kitchen to spread to King Robert’s two great halls above!

Could our kitchens have actually been located outside the main body of the castle?

This point leads us to consider that the cooking areas could well have been located outside the main castle building. Since this version of Dundonald Castle was built over the remains of Alexander’ 4th High Steward of Scotland’s Castle which had been forcibly destroyed to avoid English occupation c. 1289 during the wars of Independence, so its important to note that parts of the erection of this fourteenth-century tower house, was built using the remains of what was thought to be the west gatehouse of Alexander’s castle. By the fifteenth century renovations to the Tower House included the addition of the south tower which was an extension more or less where we might imagine the kitchens and any other ancillary buildings could have been. However if we take a look at other castles, it seems that kitchens were generally speaking located in separate buildings outside main castle buildings – with thick walls between them as we might assume – as an extra precaution against fire. At Kenilworth Castle there was a separate privy kitchen building only used for the preparation of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster’s food! We can’t be sure if Robert II also his own privy kitchen, but this may have been the case.

There was often the addition of a covered arcade or walkway for which food would have been carried inside the main building to reach the assembly of diners inside. It could be then that the kitchens at Dundonald Castle were in separate buildings somewhere inside the inner court yard, and yet we would imagine near enough to the entrance door to ensure the great trenchers of food, often served in many courses, would have stayed warm on their journey from the lower levels, up the servants stairs, to reach Robert II and his Queen Euphemia – who would have dined on a raised Dias seating area. We have assumed this to have been placed at the south end of the hall since this was nearest to the largest windows either side of the room to enjoy the most light, nearest to the fires for warmth – but not so near as to singe the royal clothing – and yet maximising comfort by being the furthest place to be away from the servant’s stairwell to avoid draughts!

Interestingly, at that time, the closer you were permitted to sit to the king, the more elaborate the food you would expect to eat, and so it must have been a steady rush of feet passing along, what may have been a corridor on the lower level, leading straight to the stairs. We bet they wished for a dumb-waiter to carry the food up and down, and given that the stairs themselves are irregular heights – said to have been deliberately built in this way to make life more difficult for would-be attackers – the servants’ job would not have been an enviable one!

It was thought that the king and queen and their important guests at the high table would be served first. The other important guests would have sat on benches alongside long tables either side of the room, placed further from the draughts of the stairwell, and served according to importance in the pecking order. We might imagine that the lowest-ranking amongst them may well have found their meal cold and unappetising once it reached them!

If outside the castle interior, where could the kitchens have been located within the inner-courtyard?

First of all, before considering where an exterior location of the kitchens might have been, it is important to note, that below the north side wall, we find there would have been the unpleasant accompaniment of the latrine chutes! This was where the outflow drop for the toilets were located! And so we can’t imagine that the kitchens would have been built anywhere near there. This only leaves the opposite side of the inner courtyard as the most likely position for the kitchens and ancillary buildings, which may have included a bakery and even a bathhouse – which were commonly placed near the kitchens for the practical heating of water, as well as that the kitchens would have radiated heat to make bathing a nicer experience, especially in winter! But of course this can’t be certain.

So what then was the lower floor to the castle used for, if not for kitchens?

Royal Dundonald Castle would have required the storage area for enormous quantities of food, beer and wine which the king’s household would’ve required. This means that the ground floor area, and cellars which are thought to reside beneath it, may well have been divided up into several ‘rooms’ with one used for example, as the Buttery – whose name comes from butts which was the original name for barrels of ale – with the servant in charge of it known as the Butler. There may also have been a Bottlery where bottles of wine would’ve been stored. We find one end of the room has the remains of a domed ceiling built into the wall – shown clearly in the short film – which was the perfect shape for storing barrels! There would have been a pantry containing the perishable foodstuffs – and given that there was little light getting into this lower level space, foodstuff would have stayed fresh longer where the lack of light would’ve made the area cold. Noting too, the existence of the arrow loops – defence of the food store may well have been considered too!

So what would they have been cooking in the castle kitchens ?

Let’s imagine the huge cooking pots bubbling away as herbs, vegetables, grains and whatever meat was available were added, to finally end up with a stew, as the most commonly prepared dish. This seemed to have been the most efficient use of firewood for cooking and a stew type dish meant there was less wastage of precious nutrients from the cooking juices. Other meals were described as a rather ambiguous pottage – which was basically anything that came to hand – mainly eaten by the servants – with a bowl of broth, some bread, a little ale, and hunk of cheese on a good day!

When we think of medieval cooking we often think of pies – but it’s unlikely that 4 and 20 blackbirds were baked in a pie at Dundonald Castle since it appears that pies didn’t arrive on the table before the 15th century – with the invention of pastry, which was then referred to as huff paste.

Royal Dundonald Castle kitchens would have prepared venison, as well as rabbits – which first came to Britain with either the Romans or the Normans – taking over as the years went by from the indigenous hare population – although hare would have been a popular culinary contribution. The nobles traditionally enjoyed game such as wild boar – once common in this type of wooded landscape, until it’s thought to have finally succumbed to over-hunting in the 13th century – so it’s difficult to say if Robert would’ve eaten much of it that he’d hunted himself, but a few may well have remained as fugitives in the Ayrshire countryside!

Meat from wood pigeon, swan, squirrel, beef, mutton, chicken, duck, goose and even peacock were a popular choice for a medieval feast. Herring and cod – smoked, dried and salted for storage – would’ve been the main source of fish, given that Dundonald isn’t too far from the sea, meaning that it could’ve been fairly plentiful. Religious institutions such as priories and abbeys were a good source for home-grown vegetables. Crusaders returned with a variety of new foods like raisins, dates, spices and figs to add to the medieval diet. Gathered fruits such as berries, apples, pears and crab apples – used to make verjuice – a popular sour juice obtained from crab apples, unripe grapes, or other fruit, was used in cooking, and in medicine. Wild plants such as dandelion, nettle and lavender would have been gathered nearby to add flavour and nutrients to meals, with the addition of herbs such as sage, rosemary and parsley probably being grown to pick readily at the castle. These would have added flavour and substance to the dishes – with salt being used sparingly, since it was a highly prized commodity used for preserving food.

If we can imagine life without potatoes – no mash or chips – since the potato didn’t come to Scotland until the 1530s, and so barley, oats and rye were ground to produce flour for bread for the poorer people, with the high society commandeering the wheat-made bread. Bread was used to bulk up a meal and to mop up the extravagant sauces which the medieval gentry would have to accompany their meat. This meant the need for huge quantities of bread – so this makes it more likely that we would have found a bakery at the Castle too.

Castles usually had their own fishponds to supply trout, and the local rivers and lochs would have also been a good source of fresh fish. Medieval castles often had bee-boles which were alcoves built into exterior walls, where woven basket hives named skeps allowed for the production of honey – which was the main sweetener for the medieval kitchen in the days before sugar arrived on our shores. It seems too that what people ate was highly influential in dictating the standard set to define the noble classes all over Europe in the medieval period. This meant the extreme use of highly spiced food, vinegars and wines, combined with items such as almonds, ginger, black pepper and honey which began to be used in abundance to provide rich, probably excessive flavouring for soups, stews and sauces!

A dish, unappetisingly named wortes, appears to have been a popular choice served as something of a medieval salad – this was cabbage, leeks and parsley boiled in a pot until tender, with butter and slices of bread added before it was served. Let us know what you think of it if you try out the recipe!

So we haven’t exactly been able to categorically define the answer as to where the kitchen in Royal Dundonald Castle was, but we have shone some light on the options as to where it could have been! We hope that you will come to see it for yourself, and maybe you can help us to answer the mystery of the King Bob’s kitchens!

The kitchens of Dundonald Castle are one of the many questions that we hope to be able to answer with our ongoing community archaeology programme. This programme is run in partnership between Friends of Dundonald Castle SCIO, Historic Environment Scotland and CFA Archaeology. For the latest updates, you can check out the dedicated archaeology page on our website: https://dundonaldcastle.org.uk/archaeology/

Find out more: An excellent example of a medieval kitchen can be found at Stirling Castle https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Attraction_Review-g191266-d13966579-Reviews-Great_Kitchens-Stirling_Scotland.html

Sources

http://www.historynaked.com/medieval-kitchens/

https://www.castlesandmanorhouses.com/life_04_food.htm#preparation

http://www.greneboke.com/recipes/wortes.html

https://www.abdn.ac.uk/sll/disciplines/english/lion/castles.shtml

Images

Cover image by Gwen Sinclair for FoDC; interior of Dundonald Castle by Jason Robertson; medieval cooking pot Image by M W from Pixabay; spit roast image by Bernd Hildebrandt from Pixabay

Imaginary Dundonald Castle site map by Gwen Sinclair for FoDC

Medieval Kitchen utensils image by Nadine Doerlé from Pixabay

Medieval Kitchen image by Gianni Crestani from Pixabay